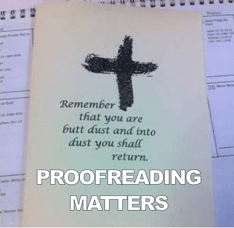

Muphry’s Law and What to Look Out For

Muphry’s Law and What to Look Out For

The author sent me a copy of her published manuscript. The acknowledgements page thanked several notable people, including her editor. I squealed with delight and flipped through the pages, coming to rest midway through the book. A typo glared up at me.

I groaned and shut the book.

Yes, the editor was me.

“Murphy’s Law” states “If something can go wrong, it will.”1 For the sake of people cringing the world over, it’s been extended and adapted to various industries, including editing.

The similar and equally cynical “Muphry’s Law” is a summary of four editorial principles:

- If you write anything criticizing editing or proofreading, there will be a fault in what you have written. (I call this the Prepare to Eat Crow principle.)

- If an author thanks you in a book for your editing or proofreading, there will be mistakes in the book. (Also known as Inflate and Deflate, as illustrated by the first paragraph of this post.)

- The stronger the sentiment in (a) and (b), the greater the fault.

- Any book devoted to editing or style will be internally inconsistent.2

If you, like me, can confirm the truth of these statements, welcome to a large and humble group of people who love language even though it trips them up.

For the sake of reducing Muphry’s Law from a jack hammer to a mosquito-buzzing level of frustration, here are a few stumbling blocks we often miss in our own work.

Proofreading Hazards:

- The beginning: Headlines or titles, first lines and first paragraphs, on the first page of copy or in the first few lines on a new page. You’d think the first bits and pieces would be the best, the freshest and fancy (or typo) free. Maybe it’s that our initial excitement makes us temporarily blind to our faults. Regardless, beware the starting points!

- One error. Typos of a feather…stick together. They’re like ants or cockroaches or Costco samples. Where there’s one, there’s bound to be another. Typos often come in pairs or small middle-school-like cliques. We will neither confirm nor deny that they are also laughing at you.

- Letter and number sequences. As easy as A, B, C…1, 2, 3. Check alphabetical and numerical lists, whether in main text, numbered/lettered headings, page numbers, footnote numbers, figure/table numbers, etc., with a fine-toothed comb. This is especially important when a list covers multiple pages. If your writing uses flowcharts or other graphics, make sure they make sense and follow the same order as any corresponding sequences described in the text.

- Dates. Calendars are simple enough. But because our brains are made to complete the familiar, we’ll often fix something wrong with days of the week or dates without realizing it. I remember staring at a calendar for what seemed like hours before realizing a date read “29” instead of “20.” I’ve even found mistakes in calendars I’ve bought. Try reading the numbers aloud, one by one, to break up the potential to “autocorrect.”

- Math. Numbers again, though more specifically, numerals. Maybe it’s easier to make errors because we’re switching from one skill to another. Or our left and right brain hemispheres are just refusing to cooperate. We’ve seen lots of errors in numerals with dollar signs, percentages, fractions, and totals, including misplaced decimal points. So break out a calculator and go through them slowly and carefully. Then do it again.

- Paired punctuation. Quotation marks, parentheses, brackets and the like are used in pairs. It might be because they’re small, but we often create what I call “little orphan Annies” by leaving out one. The ending (or closing) mark is usually the one left off. If the first is on a different line than the second, it’s a really easy mistake to make. So keep a sharp eye out for punctuation that demands a twin.

- The abnormal. Anything that stands out. Anything that’s different—text in all capital letters or in a font or style (italics, bold, etc.) that varies from the main text. Different often means harder to read.

- Everything you write. We’re ending where we started. If you’re a writer, editor, or proofreader, or you’re sending an important text, judging someone, writing a grocery list, composing a love letter, or posting on social media, please refer to Muphry’s Law and the fact that we told you so.

We are now amply paranoid and await your comments on the several missed errors in this blog post. Be merciful.

We’ll be covering our favorite grammar/word games in an upcoming blog post. If you have any suggestions to add to the list, feel free to submit them!

1 Though this is a generally known principle, for a history of its development and use, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Murphy%27s_law, which features multiple original source links and interesting context.

2 The original publication of this principle is no longer available at the original source website, but a replication can be read here at https://www.editorscanberra.org/muphrys-law.

Credit belongs to Terri Porter for the original 8 Proofreading Red Flags, which this blog post was based on.